Mental Illness: Nature or Nurture?

Thump. Thump. Thump. You can hear your heart beating out of your chest. You realize you’re having an anxiety attack. You think to yourself, “why is this happening to me?” After a few minutes you’re able to calm down. The question still lingers in your mind: how does anxiety occur? Part of you thinks you were born with anxiety, the other half thinks that something caused you to develop anxiety.

Well, what if it’s both? What if there was a scientific explanation for your questions? Recent research shows how scientists are beginning to look at mental illness through a different perspective. They want to change the narrative of mental illness being a debate between being born with mental illness or developing mental illness as we develop to a debate of mental illness coming from both sides; the genes are inherited and the environment we’re in affects our mental health and how our brain functions.

Looking From a Different Perspective

For decades, scientists have been looking for a genetic connection or pattern that can be identified in patients with mental illness. Without any luck, they have yet to find a genetic code or DNA pattern that acts as a switch to have us develop mental illnesses. This reason causes scientists to take a different approach involving etiology, what causes diseases to occur, and genetics. This new field, or subtopic of genetics, is called epigenetics and is described as the study of how people’s individual experience and environment affects their genetic functionality.

Because the majority of the research on how the environment affects our genetics is still relatively new and ongoing, scientists are inferring that exposure to environments cause stable changes in the genetic expression which in turn affect our behavior. When it comes to the research, the epigenetic studies of mental illness tend to be studied at the early stages of developments. The reason for this being that the way the changes in genetic expression is different depending on your development and adult exposure. The topic of mental illness is a very broad one containing many different disorders and the research that goes into epigenetics ends up being specific to certain disorders.

To an outside perspective, it could be seen from afar that it would make sense for mental illness to be something developed by both the experiences and through genetics. For example, twins share similar genetics but if one develops mental illness, the other twin might not develop the same illness. Meanwhile, people go through different experiences and each one can induce extreme stress that causes these illnesses to develop. Speaking from personal experience, I was diagnosed with anxiety at a young age. To me, I view it as being born with anxiety. On the other hand, knowing someone close to me had developed a mental illness due to a high stress level event that was traumatic. So, to see the connection and the differences in the way people are developing mental illnesses it makes you wonder how all of this works.

The Science Behind Epigenetics

So, how does all of this work? It works by altering how our cells use genes, the environment makes their mark on us. It’s important to note that our DNA isn’t changing entirely. When our genes are altered, it changes the gene to behave differently and is often a long-lasting change.

Scientists have put a lot of research focus on DNA methylation, which is a chemical reaction in the body in which a small molecule called a methyl group gets added to DNA, proteins, or other molecules. The addition of methyl groups can affect how some molecules act in the body. In short, DNA methylation can serve as a repressive or activation mark for genetic expression. This is important to the epigenetics behind mental illness because some of the alterations caused by DNA methylation are most likely involved in regulating how our brains react to stress, communication, and its development.

In a recent study, a group of scientists examined DNA methylation patterns in deceased people who were diagnosed with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia and from those who were mentally healthy. The results of the finding was that one in every 200 had a different methylation reaction in people with the illness listed than those that don’t have these disorders. The scientists infer from their finding that multiple genes are regulated differently in people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. (Saey, 2008)

DNA methylation is just one of many ways that an epigenetic change can happen. Taking a deeper look at our genetics, our DNA has proteins that are chromatin. One of these proteins is called histone. This protein has many different uses in the body. For example, it’s used for binding DNA together and giving its shape we know it to be and it also helps with determining which gene will be activated or deactivated for expression.

Histone is one of the more common proteins that get targeted for modification. This is important because the methylation of histone determines which genes get turned off or on. In a study mentioned by Saey in her article, they found that changes in the chromatin (which may include histone) around a gene are linked to depression and addiction. The scientists conducting the experiment did it by observing mice getting bullied where the activity level of a specific gene (BDNF) falls drastically to one-third of the level of a non-stressed out mice. Because of this, the stressed out mice would avoid socializing with other animals, similar to how we respond to socializing with depression. They took a closer look at the chromatin controlling the BDNF’s activity levels when it changed and saw that the stressed out mice had higher levels of histone methylation than the non-stressed mice. This study done on rats can be used to compare how we react to stressful/traumatic exposures like bullying and just how far the extent goes in our development.

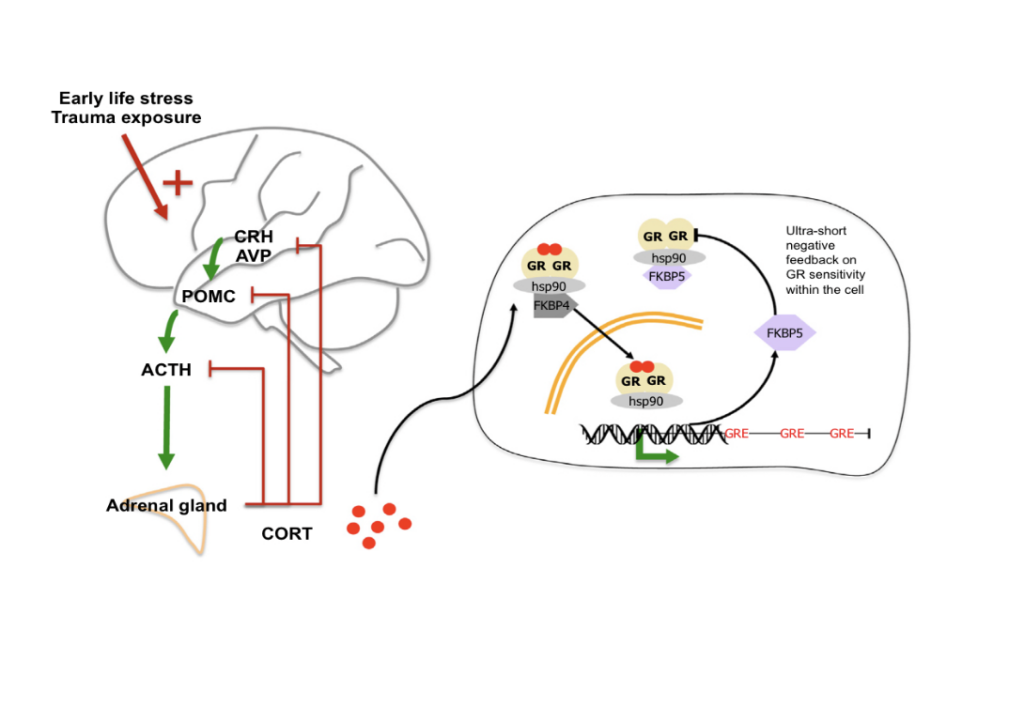

Many different situations, especially in our developing years, can leave long-lasting effects on us like how we function and how we think. These situations are, but not limited to, situations of abuse and neglect like bullying. These situations of high-level stress have all been “associated with long-term changes in the regulation of the stress hormone system.” (Klengal, 2015) The figure below shows how stress and traumas that happen early in life activate the stress hormone system and may epigenetically program the system toward alteration of the hormonal response to even minor stressors. The model below, with a lot of oversimplification, describes how the CRH and AVP hormones become active in response to the early life stress experience. This causes the release of ACTH into the adrenal gland and the cortisol binds to receptors in the brain. This influences the expression of many genes that respond to stress, metabolism and immune function. This shows how our body is reacting to our environment and the effects that come with it, that our bodies are experiencing changes because of what we go through mentally.

With more research coming from epigenetics, scientists and psychologists are hoping that with the findings in epigenetics, it can be interpreted to help in therapeutic ways. The National Institutes of Health is sponsoring about 100 studies looking at the relationship between epigenetic markers and behavior problems such as depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. (As Life Alters Genes, Illness May Emerge, 2010). Epigenetic research in mental illnesses in general is looking to provide people with relief through medicine that can potentially interrupt or reverse these epigenetic changes.

Conclusion

So what’s the verdict? Unfortunately, a lot of research is still underway and scientists are discovering new information about how epigenetics work and their connection to the origins of mental illness. However, it seems as though a lot of the research discoveries are showing that there is a connection to the environment’s effect on us genetically. From an optimistic point of view, the research being done has the potential to change the lives of millions in terms of how they view themselves or for their treatment plans.